Apple's Health Records feature is a low-profile medical win in a year of losses

Source: Apple

When Apple announced Health Records on iPhone back in 2018, I slept on it. Not because I didn't think it was a super compelling feature that would benefit millions of Americans, but because it was going to benefit millions of Americans, and I'm Canadian.

See, healthcare is a continuity, one that's deeply personal and private. While I may blurt out on Twitter that I'm headed to the dentist or an optometrist, the specter of vulnerability lingers over visits to the doctor, or to a hospital, that keeps it internal and fraught with secrecy. So I didn't think about Health Records on iPhone because it wouldn't affect me personally, and because, as a 35-year-old man in pretty good health, I'm privileged enough not to need to think much about visits to the doctor or the hospital.

The success of the Health app correlates with the rise in popularity of the Apple Watch.

But even before today's announcement that Health Records on iPhone are now available in Canada and the UK, I'd begun thinking about our healthcare infrastructure differently. Covid has made physically getting checked up so much more difficult, and having a young child who's unfortunately needed to visit a hospital a couple of times since the pandemic began, I've seen how disorganized and fragmented it is to share information between institutions.

The genesis of Health Records on iPhone actually from the growth in popularity of the Health app, which itself came out of a need to quantify and simplify all the sense data — heart rate, steps taken, workouts, sleep, blood oxygen, etc. — generated by the Apple Watch. The Health app debuted in 2014 and became a unifying center of holistic health information for all of Apple's first-party fitness aspirations, and for third-party app developers who plugged securely into HealthKit.

But all of these data points are generated by apps and APIs that Apple monitors through the App Store; bringing in outside data, say from health institutions like hospitals or doctors' offices, is another challenge altogether.

Coinciding with the announcement, I had a chance to sit down with Kevin Lynch, Apple's VP of Technology and the person most directly responsible for bringing all of this sense data into the Health app (he's in charge of the Apple Watch, among other fitness-related projects at Apple), to talk about the implications of being able to consolidate disparate health record information into one place.

Master your iPhone in minutes

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

"Medical information may be the most important personal information to a patient, and offering a consolidated view of it is really a first step in empowering them to make decisions about their health," he said. "Whereas before this information had been stored in individual silos, Health Records on iPhone enables the user to be at the center of their health information, which is transformative."

Health Records on iPhone establishes a secure, encrypted connection with the health institution. Apple never sees the data itself.

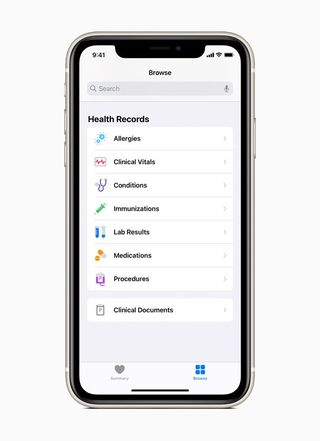

The way Health Records on iPhone works is by establishing a direct connection with a participating institution; that hospital must already have a web-based portal built with compatibility for the existing Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR, pronounced "fire") standard that's used throughout the world to securely store healthcare data.

"At Apple we value privacy so highly, we built our system to manage health data including health records in the most secure way. Health data is some of the most important and sensitive data that people have, and privacy is core to everything that we do," Lynch told me.

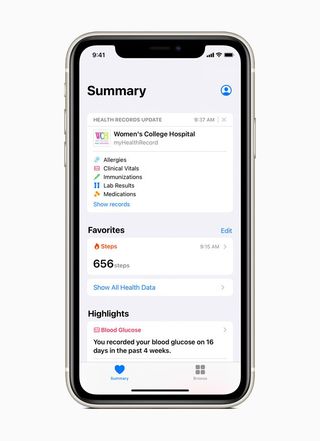

The beauty of Health Records is that it forms a persistent bond between healthcare institutions and your iPhone, but does so in a way that ensures none of the information is accessible without authenticating using passcode, PIN, or Face ID. It also brings this information — doctors' notes, test results, reports, prescriptions — into one place, and makes it interroperable with the sense data that your smart devices generate every day.

Another huge benefit — and one that was illustrated beautifully by accessibility activist and friend of iMore, Steven Aquino, for Forbes — is the reframing of healthcare data into a usable format for people with disabilities. He writes:

What Apple touts as convenient and empowering is also accessible in the disability sense. More often than not, accessing one's health information via their provider's website is an exercise in futility. Not only can the patient portals be difficult to navigate, the health records themselves can be set in small fonts that don't respond well, if at all, to screen readers and magnifiers. For anyone with a visual and/or cognitive impairment, the experience of finding and digesting their health data can be frustrating because their most personal information is literally inaccessible.

Apple's commitment to accessibility is widely known, but it's often thought about in the context of iOS. But like iPad is often more accessible to someone with limited sight than a Windows or Mac PC, an iPhone is the ideal place to interact with data that, in clinical environments, is often difficult or impossible to parse. By interacting with Apple's human interface-friendly APIs, medical centers often find their data more comprehensible when distributed through the iPhone's Health App than their own proprietary web portals.

Here in Canada, Health Records for iPhone is debuting with support for three medical centers — Women's College Hospital in Toronto, St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton, and Mackenzie Health in Richmond Hill — but given the growth arc of the U.S., which started with five and is now at 500, that number will quickly rise.

Health Records for iPhone seems to be one of those low-profile features that won't get a lot of mainstream attention, but like many of Apple's health initiatives, will have enormous implications. I may not need to go to the doctor very often right now, but I know a lot of people who are tired of dealing with frustrating web portals or faxing permission for one institution to share info with another.

Apple seems to understand and empathize with this friction, and during a year where everyone both dreads and fears having to visit a hospital, this can potentially make things just a little bit better.

Powerful health and wellness device

Adding a blood oxygen sensor and always-on altimeter doesn't seem like a big upgrade, but when paired with everything else the Apple Watch does, this is the most significant upgrade since the Series 4.

Daniel Bader is a Senior Editor at iMore, offering his Canadian analysis on Apple and its awesome products. In addition to writing and producing, Daniel regularly appears on Canadian networks CBC and CTV as a technology analyst.

Most Popular