Open vs. closed

In defending Microsoft's iOS-style 30 percent commission on apps sold on the Xbox store, Wright pointed out that the company has never made a profit on the sale of an Xbox console. That's in contrast to the profit-generating iPhone and iPad hardware and to a company like Nintendo, which doesn't take a loss on Switch hardware sales."The business model is set out to be an end-to-end gaming experience," Wright said. "Hardware is critical to delivering that experience. We need gamers to be able to have a console. We make money back in the long run on game sales and gaming subscriptions."

"Part of that [30 percent] commission goes to make it possible for us to build a console," Wright continued later. "[It's] required for us to even build the console."

Wright contrasted the 30 percent Xbox commission with the situation on the Windows-based Microsoft Store platform, which recently lowered its commission for games to 12 percent. Wright said Microsoft made this move because "there are other stores that compete on Windows" and because Windows users can "download games directly from publishers themselves. So for our Windows Store, where there are more competitors, we can't demand the same commission."

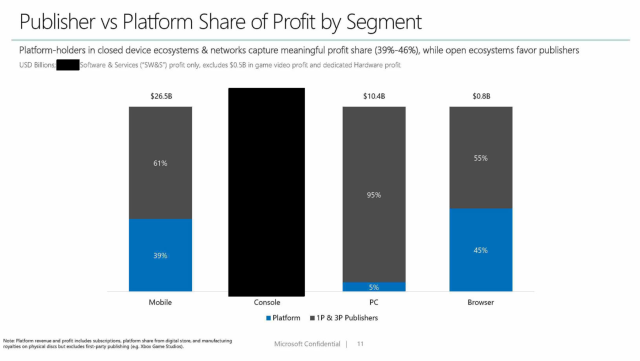

A 2019 Game Industry Profit study produced by Microsoft (and presented in redacted form at the trial) suggests that PC platform-holders capture only 5 percent of all PC gaming profits, compared to 39 to 46 percent for closed platforms like console and some mobile platforms. That's because so much of PC-based game spending flows "directly from consumers to publishers," Wright said, making "open [platforms] much more profitable for developers and publishers."

Xbox vs. Windows

Of course, the lack of competition in Xbox app distribution exists because Microsoft designed its platform that way, similarly to how Apple designed the iOS App Store. During cross-examination, Apple lawyers pressed Wright on whether she thinks it's unfair or anticompetitive for Microsoft to enforce restrictions on digital downloads, in-app purchases, or competing stores and streaming gaming services on Xbox. Apple counsel also got Wright to admit that she's not aware of any publishers, including Epic, that have complained about Microsoft's strict controls over the Xbox ecosystem.

Apple's lawyers also tried to point out the hypocrisy in the way Microsoft's restrictions on Xbox app distribution break Microsoft's own 10 principles for the Microsoft Store on Windows, as published last October.

The Xbox, Apple's lawyers highlighted through questioning, breaks the first three of these Windows-based principles:

- Developers will have the freedom to choose whether to distribute their apps for Windows through our app store. We will not block competing app stores on Windows.

- We will not block an app from Windows based on a developer's business model or how it delivers content and services, including whether content is installed on a device or streamed from the cloud.

- We will not block an app from Windows based on a developer's choice of which payment system to use for processing purchases made in its app.

While Wright said she's not an antitrust expert (and thus can't speak to the legal fairness of these differences), she defended the separate models because of one basic difference between the Xbox and PC: "How they're used and how many people they reach."

General purpose vs. special purpose

Epic's counsel took pains early in today's proceedings to confirm with Wright all the things users can do on an iPhone but not an Xbox. If you're looking for driving directions, taking a photo, ordering an Uber, or playing a game while in line at the DMV, an Xbox is not helpful, Wright agreed. An Xbox also needs to be plugged into an outlet and connected to an external screen to work, and the console doesn't have the cellular or touchscreen capabilities of the iPhone.

“Part of that [30 percent] commission goes to make it possible for us to build a console... [It’s] required for us to even build the console.”Microsoft Vice President of Xbox Business Development Lori Wright

For the Xbox and the PC, there are similarly "different reasons people use these devices," Wright said. The Xbox is an example of a special-purpose device, she said, "used for a very targeted thing." A Windows PC, on the other hand, is a general-purpose device that "can do a wide variety of things that change every day, [where] ideas are being created, [and it has] has the ability to do a bunch more things" than just run games.

Wright said the iOS ecosystem should rightly be grouped with the general-purpose devices since there is "a wide, wide variety of different ideas and applications" on iOS.

In cross-examination, Apple's lawyers pointed out that through apps and services like Spotify, Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube, Xbox consoles also do more than play games. But on redirect, Wright said that Microsoft doesn't believe people buy an Xbox for those non-gaming apps but instead are getting a game console "to play games." (Someone should point this out to the TV-on-Xbox-focused Microsoft of eight years ago).App-based streaming vs. browser-based streaming

Epic also questioned Wright on Microsoft's struggles to get a version of its xCloud streaming service listed on the iOS App Store. Wright said Microsoft tried to work with Apple to comply with the App Store's requirements for the service, including working out complicated financial agreements and technical fixes necessary to give Apple a cut of xCloud-based in-app purchases.

But Microsoft was eventually stymied, Wright said, by Apple's onerous requirement that every individual streaming game be submitted and listed individually on the App Store.

Wright said that Microsoft "wanted to use the Netflix model" for having a single subscription-based streaming game app on iOS, and the company was frustrated by Apple's determination not to amend its rules to allow such a model. "[Apple] allows Netflix to do what Netflix does, but it does not allow us to do what Netflix does," she said. "And it required making a separate application for every gaming title that has to be individually downloaded and put onto your phone."

If Netflix was put under similar restrictions to xCloud, Wright said, "Netflix wouldn't exist today [on iOS]. They would effectively not have a catalog of services that could be delivered on mobile. Every TV show, every movie would be a different application."

Microsoft eventually stopped trying to fit xCloud into the iOS App Store and rolled out a beta version of the service through iOS's WebKit-based web browsers. Wright described this as a "much more challenging experience" for Microsoft "both to build and maintain." Streaming xCloud on mobile browsers required developers to "use very complicated matrices" to account for differences between different environments that would not be necessary in a native iOS app.

Browsers on iOS, she said, are "well understood to be lacking in some of the features behind other browsers because [on iOS] you can only use WebKit—you don't get the browser competition [of other platforms]. Once you're there and you do get it to work, there are some very core elements of gaming that WebKit hasn't historically supported. It's just catching up."

“There are some very core elements of gaming that WebKit hasn’t historically supported. It’s just catching up.”Microsoft Vice President of Xbox Business Development Lori Wright

More than that, though, pushing xCloud through mobile web browsers is less than ideal, Wright said, because "the challenge is people don't play games over browser on the iPhone. Look at the data—all the gameplay is through the App Store. People are not playing games on the browser on iPhone."

In response, Apple's counsel pointed to press reviews that say xCloud is "already a super solid experience on PC and iOS," that the "overall performance was smooth and stable" on Safari, and that the iOS browser-based beta "is a remarkably polished one." Wright agreed with all of these reviews but noted that there was "a lot of work we had to go through to deliver that polish. We had to start from scratch and re-deliver" what was already working fine on a native app.

Apple's lawyers also pointed out that Apple actively helped Microsoft in its efforts to bring xCloud to iOS web browsers (Wright characterized this help as simply working out issues and bugs Microsoft encountered while porting the service for WebKit). Apple provided this support even though it makes no money from xCloud streaming on mobile browsers, as Wright acknowledged under questioning.

reader comments

306